By Jeff Christensen, CSU Stanislaus

By Jeff Christensen, CSU Stanislaus

In 2011, I had the opportunity to participate in a California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program (CCFRP) fishing trip. When I received a message from Andrea Launer, CCFRP Volunteer Coordinator, this spring about the summer data collection schedule, I knew I wanted to go out again and be part of this amazing project.

With one of my classes starting on the first day of sampling, I wasn’t able to make the Monday, August 6th date but I was aboard F/V Caroline at Monterey’s Fisherman’s Wharf before sunrise on Tuesday with hot coffee in hand ready to do some angling. After a safety briefing by Captain Shorty we headed out along the Monterey coastline as Cannery row began to stir in the light of the pre-dawn sky. The sea was a bit rough and the wind waves made the trip out to the Point Lobos State Reserve a small adventure in and of itself.

Cheryl Barnes, CCFRP Field Coordinator and MLML graduate student, gave the anglers an amusing briefing about the specifics of the collection protocols of the catch and release program. In order for this work to be helpful in determining if the Marine Protected Areas (MPA) are effective in propagating the species within these areas since their inception in 2007, a variety of anglers were assigned different lures and/ or bait similar to fishing techniques used on guided recreational fishing trips from the area.

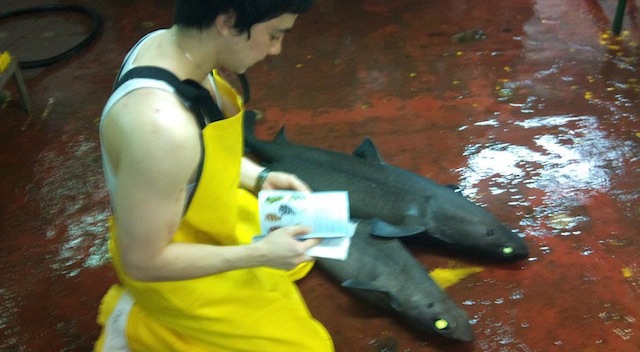

By the time Captain Shorty announced over the loud speaker to drop our lines in the water of the first research cell of the day, the rolling waves were already taking its toll on our balance and stomachs. The port side “fish feeding station” was busy early on but as the fog receded, we all got our sea legs and the fishing improved. The boat as a whole ended up catching and releasing a total of 176 fish from 14 different species, including a 84cm lingcod (Ophiodon elongates) caught by Chris L., fishing next to me. We must have been in some big fish because not too long after Chris’s lingcod, I hooked another giant fish, I estimated at over 100 cm (due to how hard it was to pull up) but after a perilous fight, the “Big One” got away as it neared the surface.

While the anglers were pulling up their catch, the scientific staff was busy collecting the fish, measuring them, tagging some, and making sure they were returned to the bottom as soon as possible. I was thoroughly impressed how each staff member tried to make sure every fish was returned to their home with human stories to tell of their own. One sea lion, however, was happy to accept a free lingcod h’ordurve as it took a large bite out of an angler’s catch as it was reeled up. That lingcod, too, was returned to the ocean making a meal for the fish, crab, and sea stars that would finish the work of the sea lion. The seas were rough as we headed back in and even tossed a few of us out of our seats to the deck (Ouch!).