By Nikki Inglis, visiting student of California State University Monterey Bay

Photos by Nikki Inglis unless otherwise indicated.

It wasn’t until the last star came out on moonless night that we heard it. At first, it sounded like the incessant wind whipping around the wooden cabin walls. Then we heard it again; a growling rasp, a ghostly whisper and so, so close. We heard wings gliding in from the Pacific Ocean and a welling up of some invisible kind of energy.

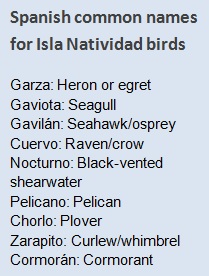

Within minutes, the sound was everywhere. The hills teemed, wings flapped frantically around us. We couldn’t see any of it, but the soundscape was three-dimensional, painting a picture of tens of thousands of birds reveling in their moonless refuge. Isla Natividad’s black-vented shearwater colony had come to life.

We had been on the island for seven days and not heard a peep. Only two shearwaters had been spotted by our group - birds that had been trapped by daylight and forced to wait it out in hiding. I was starting to wonder if perhaps they hadn’t arrived yet, and only a few early-breeders were scoping out their seasonal nesting grounds. I tried to imagine what 70,000 birds might feel and sound like, but I never imagined this. The black-vented shearwater colony on a moonless night is a singular experience, but it’s not the only reason bird researchers and enthusiasts are interested in Isla Natividad. This remote desert island is a haven for seabirds and houses a myriad of rich desert habitats—largely free from human disturbance—that offer fascinating insight into distributional patterns, morphology and behavior of familiar and uncommon species.

Nesting black-vented shearwaters

Ninety-five percent of the world’s black-vented shearwater population nests at Isla Natividad. The shearwater colony covers about 2.5 sq. km. on the southern tip of the island, surrounding the town center and lining most of the roads on the island. You can hardly take a step without running into a shearwater nest, so those steps must be taken carefully. Walking off trail is strictly forbidden, and even headlamps at night are discouraged in observance of the bird’s extreme and almost pitiable sensitivity to light. Recent aerial surveys indicate that there are about 35,000 nesting pairs of shearwaters on the island each breeding season, which runs from March to August. On Natividad, the locals call them “los nocturnos.” The locals’ pride over the nocturnos is contagious. They are adamantly protective over the colony, and there’s even a shearwater mural in town emblazoned with the words “vivan los aves.”

The nocturnos are so sensitive to light that even bright moonlight will keep them underground or out on the water. Wait for a waning moon—when the sun sets before the moon rises—and sit on a dark beach. It’s worth a trip to the island just for a brief window of moonless night to wander through the otherworldly din. Quiet just won’t sound the same afterwards.

Other seabirds

If the awe of the shearwaters’ immense but invisible presence wears off—and it might not—the island’s other bird-related curiosities offer endless exploration. I see massive flocks of brants offshore. Divers on the boats that rounded the northern tip of the island noted double-crested cormorants on the rocky cliffs. Brown pelicans strut indignantly around beaches and glide in squadrons over breaking waves. At one time, least and Leach’s storm petrels nested here. It’s still unknown if they’ve returned since nonnative threats (ie, feral cats) have been eliminated. Researchers are also interested in whether Xantus’ or Craveri’s murrelets are nesting there now. Circumnavigation of this wild island by panga could definitely yield some notable sightings to any intrepid birder.

Shorebirds

The sunrise casts a pink tinge on the tide’s fizzy froth. With each ebb and flow, a flock of plovers forage in the wet sand, scattering as the water nips at their feet.

I spent several afternoons in the intertidal, where I watched great egrets forage in tidepools draped in kelp, and whimbrels sink their long beaks in the sand. I spotted a tri-colored heron, another bird for my life list, as they don’t make it much further north than this. There are several species and variations thereof on Natividad that can’t be found in central California.

There is a notable pattern in bird ranges in which some species from the east coast of North America snake around through the Gulf of Mexico and pop up over in the Gulf of California and the west coast of Baja, but rarely make it into southern and central California. For example, this pattern is why, on Natividad, the oystercatchers have white bellies. They’re American oystercatchers, and they’re commonly seen in the on east and southeast coasts. But further north in alta California, the black oystercatcher takes over. True to its name, it’s solid black as night. It’s perplexing, as the ecology of Baja’s pacific coast is much more similar than to California is to that of the Gulf of Mexico.

It almost seems as if some of these birds observe the U.S.-Mexico border, and want to avoid the Tijuana traffic as much as we do.

Desert birds and raptors

Ospreys rule the island. Nests occupy almost every power pole in town. During our visit, one osprey nest between the store and the laborotorio, was a constant source of entertainment. Mom, dad and two fledglings lived out a mini reality show that featured nest-building, the occasional argument and one confused teenager on the ground looking up at his nest in frustration.

Away from shore, the seemingly barren scrub and cactus forests come alive with lark songs. The horned lark will look familiar to California birders. Petite but statuesque, these songbirds are instrumental in the desert soundscape, balancing out the honks of the seagulls with their delicate tune.

Ravens patrol the skies over the island, roosting ominously at the lighthouse, making bold, throaty calls and sending the resident rodents cowering in their burrows.

Pack your binoculars and field guide and make the walk up to the lighthouse that crowns Isla Natividad. On the short hike, you’ll pass through seagull colonies and be subject to their insistent harassment. You’ll watch hunting raptors rocking in the sea breezes. You’ll see blue water in every direction and the flocks of seabirds beyond the breaking waves. And you’ll understand why these creatures fly so far just to be here.