By Ann Bishop, Phycology Lab

This year the Baja field class traveled to Isla Natividad to experience a giant kelp forest at the southern end of Macrocystis pyrifera’s range. Looking from the surface, the waves of turquoise water and the tendrils of sienna scimitar blades mirror those of Monterey Bay and of Southern California. It’s only once you dive beneath the surface you can begin to understand that we are not in Monterey anymore.

The Monterey Bay kelp forest has its own structure of over story, understory, and benthic covering seaweeds. But, these layers and the species that develop them are not always so clear cut- based on a patchwork of substrate and exposure to the storms. Much like an eastern forest can be a mix of deciduous, conifers, shrubs, and meadows.

The kelp forest on Isla Natividad, is less this patchwork and more like standing at the bottom of an old growth rainforest. The kelp grows in thick stands, sometimes so dense that becoming tangled and un-tangled is a habit rather than an event. The understory Ecklonia grows in incredible abundance. Their waving blades create the impression that the bottom is right there, maybe not even a hands breadth away. But, instead it hides yet another layer. Underneath the Ecklonia, are a fascinating array of wine-red algae, feathery pink corallines, gorgonian fans, anemones, sponges, and most unlikely of all- rotoliths! These slow growing crustose coralline algae are often mistaken for rocks rolling across a sandy plane, but here they were, thriving under their towering brown cousins.

Like their terrestrial counter parts, these forests reflect the impacts of the human communities who rely on them. Isla Natividad looks the way it does today because of the careful management practices and intense love the people have for their island. The willingness of the co-operative to learn, flexibility to adapt, coupled, with their ability to exclude poachers has resulted in the rich underwater world we were permitted to visit.

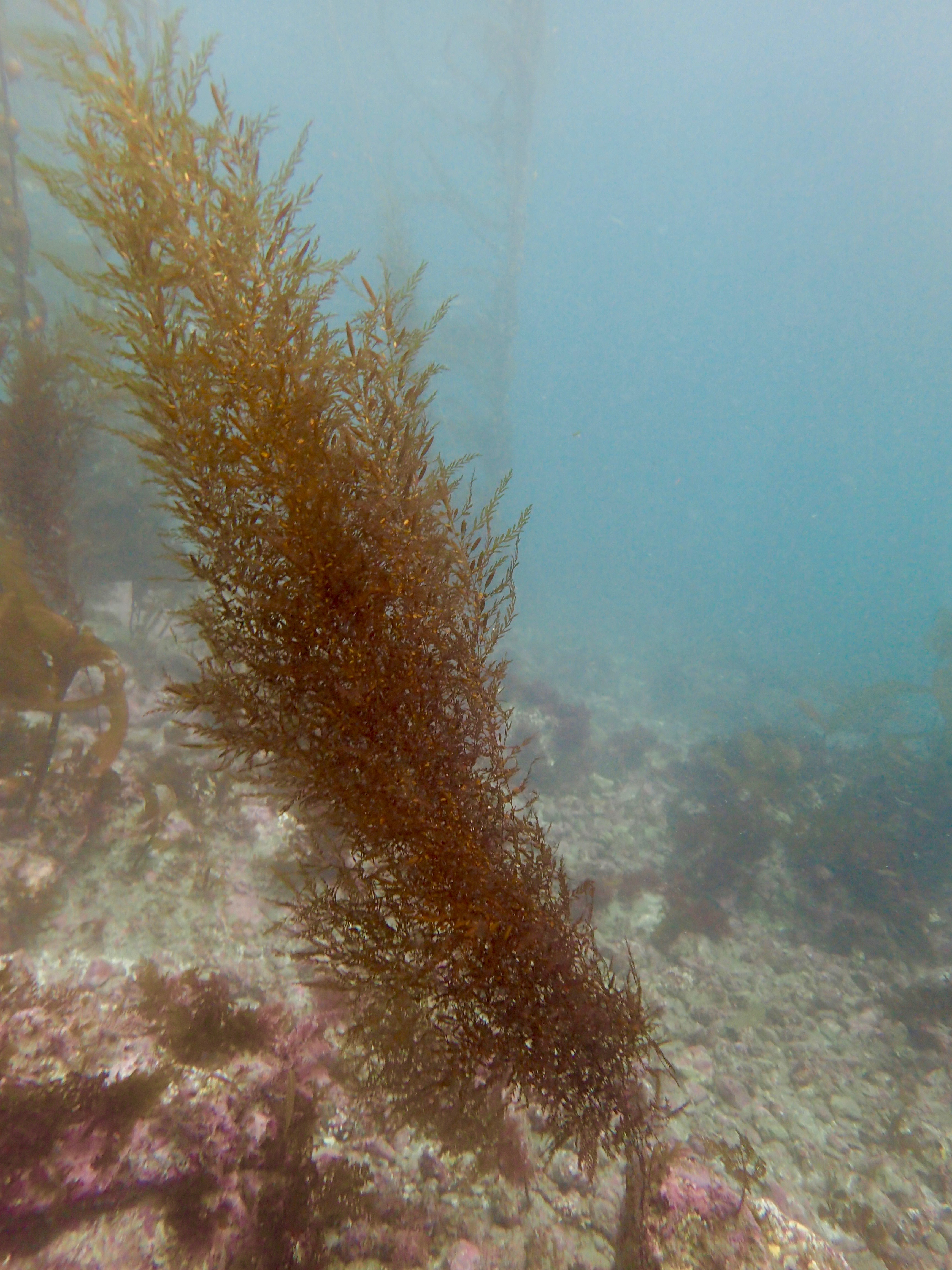

Yet, even the best laid plans and managers can face new challenges in the changing oceans. Other kelp forests, faced with warming seas have been heavily impacted by an increase in invasive species. Invasive seaweeds Sargassum horneri and an aquarium variety of Bryopsis to name some of recent new arrivals. The impact of invasive that may be familiar to Californians might be the difference that can be seen in the growth of S. horneri on Santa Catalina, off the coast of Los Angles, before and after the 2015 El Nino.

On Isla Natividad, both these invasive seaweeds are present but, fortunately have not been able to dominate the island. At least not yet. My project focused on identifying and quantifying where S. horneri was present around the island. While only a few of the sites we explored contained S. horneri, I am hoping the data from my project can assist with monitoring and future management. Knowing the baseline of an invasive species gives the managers important information and tools should those species begin to take the place of the native and endemic species. With knowledge, management, and a little bit of luck the community of Isla Natividad will be able to fish, share, and protect their underwater forests for generations to come.