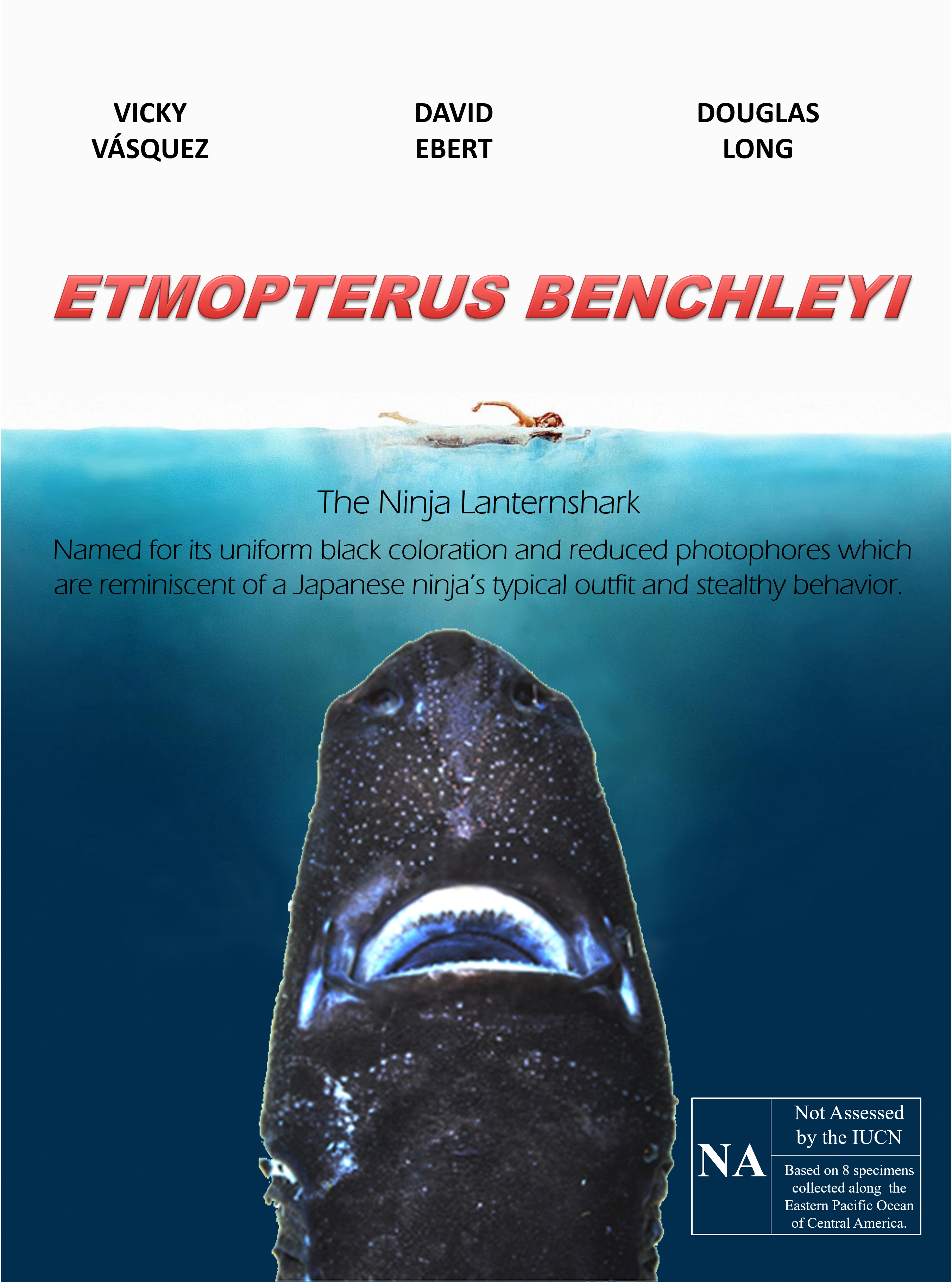

By Vicky Vásquez

On December 21st, 2015, another ‘Lost Shark’ was officially found by the Pacific Shark Research Center (PSRC). PSRC is one of the world’s leading labs in chondrichthyan taxonomy research and I had the opportunity of being lead author on the paper for this discovery (how sweet is that?!). For this study, I described a new species of dark-sleek Lanternshark from the genus Etmopterus. And the coolest thing about describing a new species? Naming it!

When I was given that chance, I didn’t hold back. This is the story of how the Ninja Lanternshark got its name.

Let’s begin with ‘Lost Sharks’. The term was created by my professor and co-author, Dr. David Ebert to identify lesser known species that attain little public or scientific attention. Examples of more charismatic species would be Great White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) and Whale Sharks (Rhincodon typus). The genus Etmopterus and its 38 species (current to the publishing of this post) are a perfect example of the ‘Lost Shark’ dilemma. That’s because despite being one of the most speciose genera of sharks in the world, it is also one of the least studied. Common names, though not official, are another reflection of the anonymity the Etmopterus genus faces. Names like Brown Lanternshark and Lined Lanternshark are certainly helpful in describing the shark’s appearance but they are not particularly memorable. But that’s not even the main issue! My gripe is with the fact that there are two Brown Lanternsharks (E. compagnoi and E. unicolor) and two Lined Lanternsharks (E. bullisi and E. dislineatus). To be fair, overlaps in common names happen a lot (just Google ‘Yellowtail’ and see how many different species you get). More so, they can even change overtime for a particular species. To avoid confusion, this is why many scientists are far more interested in the universal and permanent scientific name (assuming no changes occur to the status of the species). However, in the case of Lanternsharks, these are deep-sea species people rarely see and therefore rarely talk about. For just a moment, let that sink in- there are 38 relatively unknown species of shark that GLOW IN THE DARK. If that’s not cool enough, they even have spines on both their dorsal fins for protection. So why are spine-wielding Lanternsharks not getting any attention? The answer is certainly up for debate but overlapping common names are certainly not helping. To be fair, there is one more very good reason why common names get so little consideration in taxonomic papers.

Confirming the discovery of a new species consists of hard tedious work that takes a long tedious amount of time…. trust me.

Luckily, in the case of the Ninja Lanternshark, my other co-author, Dr. Douglas Long, has you covered with an easy and exciting read. Delving passed the Ninja Lanternshark, taxonomic research often involves the examination of a much larger picture. For instance, work conducted in the lab of Dr. Gavin Naylor aims to describe the entire chondrichthyan tree of life. Despite the small ripple I was making in the sea of chondrichthyan taxonomy, I still felt like I was a part of a huge moment. I was confirming the discovery of the very first Lanternshark ever found off the Pacific Ocean along Central America.

"What's in a name? That which we call a Lanternshark by any other name would glow as bright." -Sharkspeare

Of equal weight on my mind was therefore the concern that such an interesting discovery was doomed to the ‘Lost Shark’ fate. It was actually Dr. Long who gave me the idea to think innovatively. For a different taxonomy project, he chose the common name Jaguar Catshark, after the fictional shark in the movie, Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. The decision ended up getting Dr. Long a photo with his new buddy and Steve Zissou actor, Bill Murray, which he has also written about. This isn’t the first time a clever name has received public attention. There is actually a long history of biologists coming up with attention grabbing names, though again these tend to be scientific not common names.

Side note, too cool not to mention: One of my favorite examples is the arachnologist who named a species of trapdoor spider after his favorite singer, Neil Diamond. Stephen Colbert caught wind of this story and had the biologist along with some unnamed spiders as guests on the Colbert Report. By the end, one lucky spider was chosen and named Aptostichus stephencolberti.

As I realized all the potential circling the naming process, I was PUMPED-UP and ready to give this new species a clever name! I should mention that at this point in the story, I had been going to the California Academy of Sciences for months, examining and re-examining my new specimens. I wanted to ensure my specimens were nothing like the other 37 known etmopterids; and they weren’t. These specimens were jet-black with none of the classic body marking that other Lanternsharks possess. They were also much smaller and didn’t seem to glow as bright as most other species. Thinking about a name to reflect those features felt like proof I was almost done.

Almost done? I wasn’t even close.

What if another researcher had stumbled upon some specimens too? At the same time I was sitting in a lab endlessly pouring hours of honed attention into every minute detail of every shark I had, somewhere… someone… could have been doing the exact same thing! It may sound farfetched but the threat was quite real. During background research for the introduction of my paper, I realized new species were being discovered all the time! In 2015, nine new elasmobranch species (included this one) were discovered, with most being deepwater species. When I thought about that, my work became a race against time and a shadow competitor. The first of us to publish would be the official discoverer.

Suddenly, a clever name seemed like a foolish concern. Worst, was the encroaching threat of losing the accolade entirely. My mind was flooded at the time with urgency but haste was its own kind of enemy. It’s not uncommon for taxonomists to write papers proving that what were previously believed as separate species are actually one in the same. One way an error like this occurs is when an established species is mistaken as new because it was found outside its known distribution range. Correcting or preventing such errors is often done through genetic analysis. Looking at the work I had done, I not only had something in a new region for any Lanternshark, I had no genetic analysis. Was I about to make this classic species mistake? Multiple reviews of my work was imperative to assuring my discovery would not be undone …and that takes time.

Interestingly to me, my co-authors did not seem as panic stricken by this cataclysmic, yet still theoretical, threat haunting our research. Why weren’t they more concerned?!?!?!?

Of course, it should’ve dawned on me sooner, it wasn’t their first rodeo. And quite literally so. Dr. Ebert and Dr. Long recently published another elasmobranch discovery from the very same research expedition. Like many seasoned scientists, my co-authors juggle multiple projects in collaboration with many different colleagues. So needless to say, the time-crunch I was feeling was not mutual. In fact, before I was brought onto the Lanternshark project, the specimens had been sitting in a museum for five years; again a common occurrence when there’s many projects to conduct.

Regardless if my “race against time” was as dramatic as I thought, the ‘Lost Shark’ dilemma never changed nor my desire to address it. So how did I find time to come up with a clever name amidst the race to publish our findings?

Turns out, the answer was easier than I thought! I asked four very short people for help. Well… they’re short for now. Since my little cousins are between the ages of eight and fourteen years old, they are literally growing as I type!

I had no idea how successful this approach would be. By incorporating my co-authors suggestions and a little creativity, my cousins and I came up with both a common and scientific name that drew a media storm just in time for the winter holidays! I say this quite literally as my family delayed opening Christmas presents on the 25th so the local news station could finish my interview. Most recently, the Ninja Lanternshark was incorporated in a 10-strip series (beginning here) for the comic, Sherman’s Lagoon by Jim Toomey.

The innovation didn’t stop there. My cousins and I recorded our shark conversation and we created a short film about it. I would now like to introduce you to, “We Named a Shark!” the video of how the Ninja Lanternshark got its name.