By Gillian Rhett, Invertebrate Zoology & Molecular Ecology Lab

If you saw Nate’s post last month, you may have wondered: where does a whale carcass go? Sometimes it will wash up on a beach, which is lucky for us because that means we can collect all kinds of samples and information that help us learn more about how whales live and die.

But most whale carcasses don’t wash up on beaches. Initially, the gases that are a byproduct of the decomposition process build up inside the carcass and it floats, providing food for surface-dwelling animals such as seabirds. But when the remaining tissues and bones sink to the seafloor, that’s not the end of the story!

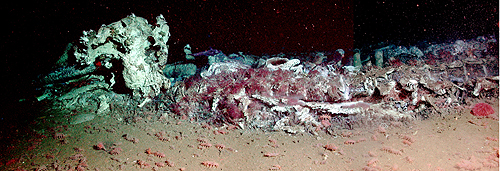

Since the 1990s, there has been increasing interest in the study of sunken whale carcasses, or “whale fall,” as a habitat for all kinds of organisms on the seafloor (1). The deep sea is a very different environment from what we’re used to here on the surface: the ecosystems we’re familiar with have photosynthesizers – plants or algae – as the primary producers, the base of the food web. But the deep sea doesn’t get any sunlight, so where does their food come from? There are a few different sources of nutrients, such as marine snow, the sunken detritus from organisms higher up in the water column, and chemoautotrophs, which can make food from the inorganic sulfur that comes out of seafloor vents. Whale fall is another source of food for these creatures of the deep.

The deep seafloor is an extreme environment, so it’s not surprising that the organisms that live there look pretty weird – for example, these hydrothermal vent snails studied by MLML alum Kyle Reynolds. One of the weird creatures that live on whale fall is the Osedax worm, which is a relative of Riftia, the red tube worms that live on deep hydrothermal vents and obtain food from their symbiotic, chemoautotrophic bacteria. Osedax worms are specially adapted to live on whale bones: (2). Another recent finding that’s really cool is that there have been invertebrates living on the sunken carcasses of large marine animals since before there were whales! Fossils of snails similar to the ones found on modern whale fall have been discovered on the fossilized bones of plesiosaurs (3).

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute’s Ventana are essential for studying these deep sea environments. The Ventana is deployed and controlled by trained operators on a ship, such as MBARI’s R/V Point Lobos. I’m lucky enough to have the chance to work with researchers at MBARI for my own thesis project. The Ventana will collect samples for me from under the whale bones, then I will take the samples back to the lab and examine the tiny organisms that live in the whale fall habitat, using a microscope and DNA testing. Who knows what I’ll find!

See these publications for more information:

(1) Smith, C.R. and Baco, A.R., 2003. The ecology of whale falls at the deep-sea floor. Oceanography and Marine Biology Annual Review 41, pp. 311-354.

(2) S.K. Goffredi, C.K. Paull, K. Fulton-Bennett, L.A. Hurtado and R.C. Vrijenhoek, 2004. Unusual benthic fauna associated with a whale fall in Monterey Canyon, California. Deep-Sea Research I 51, pp. 1295-1306.

(3) Kaim, A., Kobayashi, Y., Echizenya, H., Jenkins, R. G., & Tanabe, K. 2008. Chemosynthesis-based associations on Cretaceous plesiosaurid carcasses. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53:1, pp 97-104.